British troops capture Canton Commissioner Ye Mingchen, 1858.

As I have worked through the history of the Jarvis family (Tanner line) I have noticed that the histories that children and grandchildren left of George and Ann Prior Jarvis do not tend to be accurate in every detail. For example, the book, The Essence of Faith, contains a number of stories, particularly those about the early lives of George and Ann Jarvis, that are recognized by most readers as historical fiction, and which are contradicted by the original documents about the lives of the Jarvis family including birth and marriage records.

George Jarvis. He lost one of his eyes during his time as a sailor.

As with most family histories, the errors are probably due to children and grandchildren forgetting precise details of stories that they heard. (Although most people agree that the one about Ann being a niece of Queen Victoria was made up of whole cloth.)

So when I started working on Ann Prior Jarvis's autobiography, I assumed that she had the same sort of memory problems about her early life. This was reinforced when I took a quick look at the history of the Second Opium War, since George was in China at the time. She mentions "the massacre of the Urirepeans [European] sailers. The last Chinese war had begun with Eng[land]." I started reading histories and timelines of the war online and could find nothing to confirm that there were any European deaths early in the war.

But I kept looking, thanks to the library collection on Google Books, and I eventually confirmed her account.

A Very Brief Background of the First Opium War (1839-42)

The Qing Dynasty came into power in the 17th century and it was at the height of its powers in the 18th Century. In the 18th Century, the British Empire was trying to open all of China to British merchants. In particular, it wanted to legalize the opium trade; use Chinese slave laborers for its many plantations, mines, and railways around the world; end piracy; and open the entire country to British trade, not just selected ports.

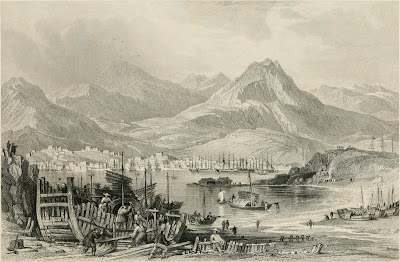

China in 1844. From Wikipedia.

But British and French and American imperialist goals began to create more and more friction with the Qing Dynasty. These foreign countries came seeking tea, porcelain, spices, and silk. China would only take silver in payment, and this was very expensive to the British trade.

Finally, the merchants realized they could import Indian opium into China and thereby even out the trade deficit. China wanted to eliminate the sale of opium in its country and otherwise protect its autonomy and culture, and in 1839, the Chinese Emperor appointed a new governor in Canton (Guangzhou), its major foreign port. Governor Lin Zexu arrested more than 1,700 opium dealers, confiscated tens of thousands of opium pipes, and destroyed more than 2.6 million pounds of opium held by foreign merchants.

A statue of Lin Zexu in New York's China Town. He is now seen as a national hero for his role in resisting European imperialism, drug abuse, and illicit trade.

The British government demanded reparation for the loss of the opium, and began the First Opium War. Britain defeated the Chinese and occupied Shanghai and forced the Chinese to accept the Treaty of Nanking, which required reparations, an unequal trade structure, and the loss of Hong Kong to Great Britain.

It was a war without any ethical justification. A young William Gladstone, speaking in Parliament, called the war "unjust and iniquitous."

A Very Brief Background of the Second Opium War (1856-60)

In the 1850s, the British wished to renegotiate the Treaty of Nanking and expand its powers in China. French and American trade treaties were also due for renegotiation. The Chinese government rejected increased demands.

On October 8, 1856, officials of the Qing Dynasty boarded the Chinese ship, Arrow, and arrested its crew. The Arrow had been registered in Hong Kong and was flying the British flag but was suspected of piracy and smuggling and its registration had expired. British officials demanded that the crew be released. The crew was released, but the British still bombarded and destroyed Qing forts and boats.

The incident started what was known as the Second Opium War, or Second Anglo-Chinese War, or Arrow War.

Chinese officers lower the British flag on the Arrow.

One of the major players in the Second Opium War was named Ye Mingchen. He was a government official in Canton (Guangzhou). As the British bombed Canton, Ye offered a bounty of $100 for British heads.

Ye's generous bounty on Europeans may have prompted an atrocity on December 29th. The Chinese crew of the steamship Thistle, which carried mail from Hong Kong to Canton, mutinied en route and beheaded all eleven European passengers, with the help of Chinese soldiers who had disguised themselves as passengers. The Thistle was set ablaze and found drifting in Canton harbor with the headless victims in the hold. The heads had been taken so the crew could collect Ye's bounty, which had risen to $100 per head. (Hanes, William Travis, and Frank Sanello. 2002. The Opium Wars: the addiction of one empire and the corruption of another. Naperville, Ill: Sourcebooks, p. 184.)

China lost the first part of the war in 1858 and was forced to sign the Treaties of Tientsin and the Treaty of Aigun. China lost the second part of the war in 1860 and signed the Convention of Peking. China was forced to accept the opium trade and make other concessions including opening further ports to Western trade, allowing the practice of Christianity in China, and allowing Britain to transport Chinese citizens under indentured servitude to America.

Hong Kong in 1843.

George Jarvis and the Opium War

When George Jarvis was in Hong Kong and China, the tensions were rising, and as he left to England, the crew was killed on of one of the steamers that could have been his place of employment.

When Br Jarvis went away the chief engineer said he would have him stay with him on the steamboat that was to run from Shan[ghai] to Hong Cong [sic] and he thought he would get enough money to emigrate us … As soon as he reached his destination the chief enginee[r] discharged him and kept another man on. Br Jarvis wanted to know if he did not please him. He said yes George but you are a married man I think you had better go back to Eng[land]. B Jarvis was vexed as he knew he would not have enough money to emigrate so he tried to get on other steamboats ... everything was against his wishes to stay in China so he went on top of a mountain to ask the Lord what to do. The impression was go home so he started for Eng[land] and the first port they stop[p]ed at they heard of the massacre of the Urirepeans [European] sailers [sic]. The last Chinese war had begun with Eng[land]. Had he stayed there he might have been one of the slain but the Lord had worked on the heart of a man that was fond of him ... and against the wishes of all he had to come home. When he returned we had barely enoug[h] money to pay our pas[s]age to Boston ...

And that situates George Jarvis's experience within the greater history of mid-19th century British imperialism. It also, along with other facts and themes which I have found to be accurate, confirms the validity of Ann Prior Jarvis's accounts.

An excellent summary of the Opium Wars. So fascinating to seen your family's personal connection.

ReplyDeleteI have always been impressed with all of your research! This was my first read about George and the imperialistic Navy he sailed for and all that which happened in China. He was lucky to get out of there! My brother in law Kelly Lauritzen and His wife begin their assignment in Guangzhou with the State Department later this year. Your article helped me to solidify my notion of visiting there. I look forward to seeing you also if possible when you come out to SLC in February. Good on you👍🏼🇳🇿

ReplyDelete